The Baal's Bridge Square by Bro. Philip Crossle,

The Builder Magazine, 1929.

Pictures and photographs inserted by Irish Masonic History and Jewels.

One of the most curious relics of the ancient Craft of Freemasonry is the so-called Baal's Bridge square, now in the possession of Union Lodge, No. 13, Limerick. A brief account of it, with a wood cut illustration appeared in the Freemason's Quarterly Review, for August, 1842, contributed by Bro. Furnell. There was another article upon the same subject in the Freemason's Quarterly Magazine and Review for 1850. The Square does not appear to have been published again till 1925, when a full size drawing made from a rubbing of the original appeared in our History of the Grand Lodge of Ireland. This was later reproduced in THE BUILDER for May, 1927, from a copy of the drawing furnished by the late Bro. Simpson. The accompanying illustration is from photographs taken by myself, at Limerick, to which place I went for this express purpose. The illustration is the same size as the square, and shows the various imperfections due to age and corrosion. The outside length of the arms are a trifle over four and one-eighth inches in length, seven-eighths in width, and the metal is less than one-sixteenth of an inch thick.

|

In a paper by Bro. Henry F. Berry read before Quatuor Coronati Lodge, published in the Proceedings for 1905 [A.Q.C. vol. xviii, p. 18] another brief account of it is given. This paper chiefly dealt with the interesting "Marencourt" Cup. For the benefit of readers of THE BUILDER who may never have read of the romantic incident connected with this, it will perhaps be not without interest to give an outline of the story. Captain Marencourt was the commander of a French Privateer, Le Furet (in English "The Ferret") which in November, 1812, captured the sloop "Three Friends" of Youghal. Marencourt gave orders that she should be scuttled and sunk; but discovering that her Master, James Campbell, was a Mason, he countermanded the order, and released the vessel and her crew.

|

In February following Le Caret was herself captured by an English frigate, the "Modeste," and Marencourt was made a prisoner. Campbell was a member of Union Lodge, No. 13, but there is no record remaining of any action being taken by it, though it is most probable that something was done, for Ancient Limerick Lodge, No. 271, passed a resolution eleven days after Marencourt's capture, thanking him for his humanity and requesting Lodge No. 79 at Portsmouth to communicate this to him, and also expressing a desire that the government might take some special steps in the circumstances. A similar resolution was passed by Rising Sun Lodge, No. 952, a week later, which in addition asked for the good offices of Lord Donoughmore, Grand Master of Ireland. This was published in the Limerick and Dublin papers.

No information remains, what if anything came of these resolutions, but later still, Lodge No. 13 ordered a cup or vase to be made to present to Capt. Marencourt, to cost "100. This was to have been presented to him in May, but before the time came he had been released and had returned to France. The cup was then sent to the Grand Orient of France, but in the meantime Marencourt had gone to Africa, where he died. The cup was therefore returned by the Grand Orient of France to the donors, and has been preserved by the lodge ever since.

No information remains, what if anything came of these resolutions, but later still, Lodge No. 13 ordered a cup or vase to be made to present to Capt. Marencourt, to cost "100. This was to have been presented to him in May, but before the time came he had been released and had returned to France. The cup was then sent to the Grand Orient of France, but in the meantime Marencourt had gone to Africa, where he died. The cup was therefore returned by the Grand Orient of France to the donors, and has been preserved by the lodge ever since.

Having related the history of this memorial of fraternal sentiment, Bro. Berry concluded his paper with an account of the relic now under consideration. This was presented to Bro. Furnell by Bro. James Pain, Provincial Grand Architect. This was the same Bro. Furnell who contributed the account to the Freemason's Quarterly Review. In this he said that Bro. Pain had in 1830 been the contractor for the rebuilding of Baal's [or Ball's] Bridge, and that it was in taking down the old structure that the Square was discovered "on the English Town side." The square was "under the foundation stone." It is a pity that more definite details of its place of concealment were not preserved, and especially whether there was anything else to mark the covering stone as a "foundation" stone, over and above the inference that it was such because of the deposit of the square under it.

|

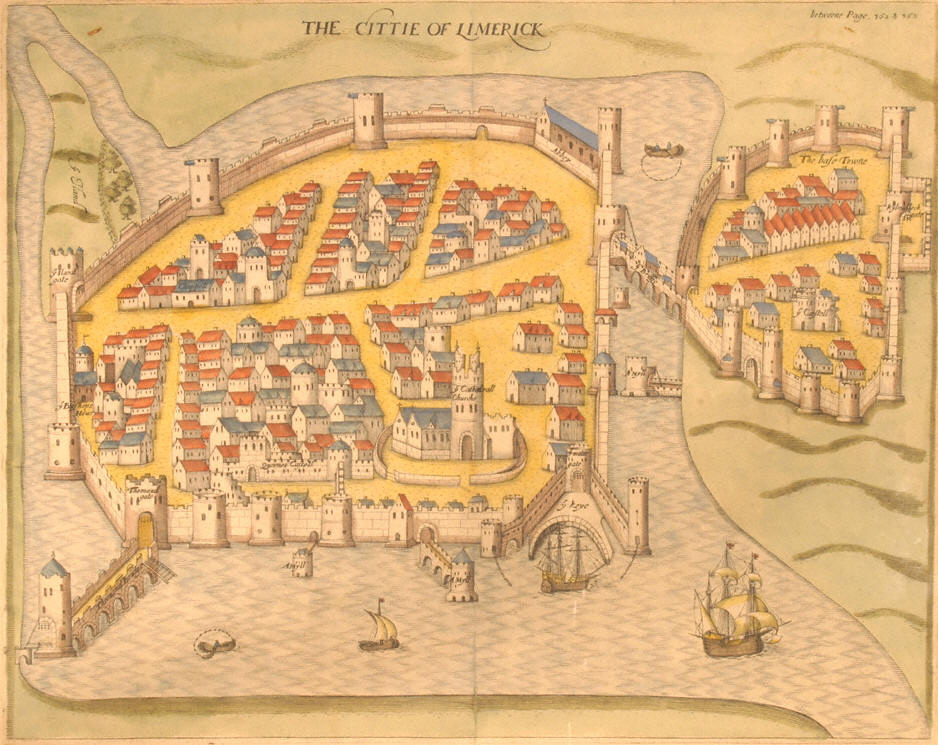

The "English Town" is on an island in the river Shannon, also known as King's Island. This is the old town, dating back to the times of the Danish conquests in Ireland. Baal's Bridge connected the island with the south bank of the river where the "Irish Town" later grew up. The square was deposited in the eastern corner of the northern pier or abutment. |

|

The illustration here given of the old bridge is taken from a drawing in the possession of the lodge, which was probably made by some member of the Furnell family. Unfortunately the ornamental border did not come out completely in the photograph. Nevertheless it gives a good idea of the old bridge with its four arches, and the houses and shops built on it. An alternative name for the structure seems to have been Thye, or Tide Bridge; which seems to have been a suitable appellation, as judging from the current represented as racing through the arches it must have been as perilous to navigate as Old London Bridge. |

.

Old Baal's Bridge

|

Bro. Furnell stated the date on the square to be 1517. With this Bro. Berry disagreed, reading it as 1507, and this earlier date has been generally accepted since on his authority, as I did myself in making the drawing for our History. But after a minute examination of the relic with a magnifying glass I am unable to agree with him. In my opinion the third figure is certainly intended for the figure one, as Bro. Furnell took it to be. It is formed in the old style, like our letter J. and the curve at the bottom is what has undoubtedly led to its having been taken for a partly defaced cipher.

The square is black with age and the inscription is not very deeply engraved. The surface is also very much corroded. These imperfections appear very plainly in the photograph.

That the relic is genuine seems to be beyond reasonable doubt. The date of the erection of the old bridge is not known. It is practically certain that there has always been a bridge of some sort to the island since the year 1174 at least, when the city came into English hands. The deposit might have been made during some repairs to the abutments if the bridge itself should be supposed older than the seventeenth century.

There are numerous instances of foundation deposits in the mediaeval period, but these are nearly all of the nature of foundation sacrifices. It was customary in ancient Egypt to deposit specimens of the building material and models of the tools and implements employed. This model square, for it is obviously nothing more, is the only known instance of the kind in the British Isles, so far as is known. The inscription, too, witnesses to a moral application of mason's working tools in a most definite way. And this is also almost unparalleled, were it not for the inscription on the ancient chest that belonged to the Steinmetzen of Hamberg, in which speculative interpretations of the square, compass, level and gauge are given, or rather alluded to [1], and which is also found on the "Master's Tablet" at Baste in Switzerland.

The iconoclasm of Masonic scholarship, while it has been most valuable in the past in clearing away many baseless imaginings, has possibly gone too far. In reality there are so many indications of something more than trade usages and technical secrets in the Masonic Fraternity that the impartial student is forced to accept them even if they remain very difficult to interpret.

NOTE

[1] See Gould, History (Yorston Edition) Vol. i, p. 168, where a translation of this curious inscription is given in full.

The square is black with age and the inscription is not very deeply engraved. The surface is also very much corroded. These imperfections appear very plainly in the photograph.

That the relic is genuine seems to be beyond reasonable doubt. The date of the erection of the old bridge is not known. It is practically certain that there has always been a bridge of some sort to the island since the year 1174 at least, when the city came into English hands. The deposit might have been made during some repairs to the abutments if the bridge itself should be supposed older than the seventeenth century.

There are numerous instances of foundation deposits in the mediaeval period, but these are nearly all of the nature of foundation sacrifices. It was customary in ancient Egypt to deposit specimens of the building material and models of the tools and implements employed. This model square, for it is obviously nothing more, is the only known instance of the kind in the British Isles, so far as is known. The inscription, too, witnesses to a moral application of mason's working tools in a most definite way. And this is also almost unparalleled, were it not for the inscription on the ancient chest that belonged to the Steinmetzen of Hamberg, in which speculative interpretations of the square, compass, level and gauge are given, or rather alluded to [1], and which is also found on the "Master's Tablet" at Baste in Switzerland.

The iconoclasm of Masonic scholarship, while it has been most valuable in the past in clearing away many baseless imaginings, has possibly gone too far. In reality there are so many indications of something more than trade usages and technical secrets in the Masonic Fraternity that the impartial student is forced to accept them even if they remain very difficult to interpret.

NOTE

[1] See Gould, History (Yorston Edition) Vol. i, p. 168, where a translation of this curious inscription is given in full.